Part I: Getting Started with Astrophysics

Welcome to the universe! In this part, we'll introduce you to the fascinating field of astrophysics, the tools scientists use to study the cosmos, and the fundamental concepts you'll need for the rest of the course.

📚 Download Chapter PDFs

Download the original textbook chapters for offline reading and reference:

Chapter 1: What is Astrophysics?

Observational vs. Physical Properties

Imagine trying to study something you can never touch, never visit, and can only see from incredibly far away. This is the central challenge of astrophysics! Unlike chemists who can mix compounds in a lab or biologists who can examine cells under a microscope, astrophysicists must extract everything they know about the universe from the light that reaches Earth.

The Fundamental Distinction:

Astrophysics makes a crucial distinction between two types of stellar properties:

Observational Properties

What we can directly measure from Earth: brightness, color, position, spectrum, etc.

Physical Properties

What we infer using physics: luminosity, temperature, mass, radius, composition, etc.

The Cosmic Distance Scale

Understanding distances is perhaps the most fundamental challenge in astrophysics. Without knowing how far away an object is, we can't determine its true size, luminosity, or mass. The universe presents us with an enormous range of scales:

Powers of Ten:

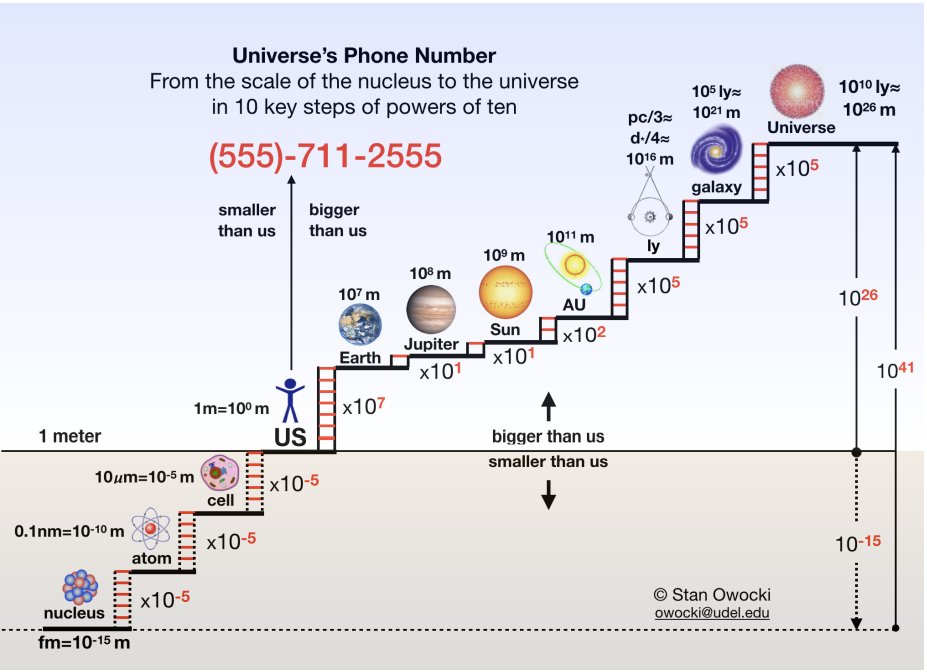

Figure 1.1: The incredible range of scales in the universe, from subatomic particles to the observable cosmos.

- • 10⁻¹⁵ m: Atomic nucleus (protons, neutrons)

- • 10⁻¹⁰ m: Atoms and molecules

- • 10⁰ m: Human scale

- • 10⁶ m: Earth's diameter ~12,800 km

- • 10⁹ m: Sun's diameter ~1.4 million km

- • 10¹¹ m: Astronomical Unit (AU) - Earth-Sun distance

- • 10¹⁶ m: Light-year (~63,000 AU)

- • 10²¹ m: Diameter of Milky Way (~100,000 light-years)

- • 10²⁶ m: Observable universe (~93 billion light-years)

This incredible range—from 10⁻¹⁵ to 10²⁶ meters—spans 41 orders of magnitude! That's like comparing the width of a single atom to the size of our entire galaxy.

Time Scales and Velocities

Just as space encompasses enormous ranges, so do time and velocity in astrophysics:

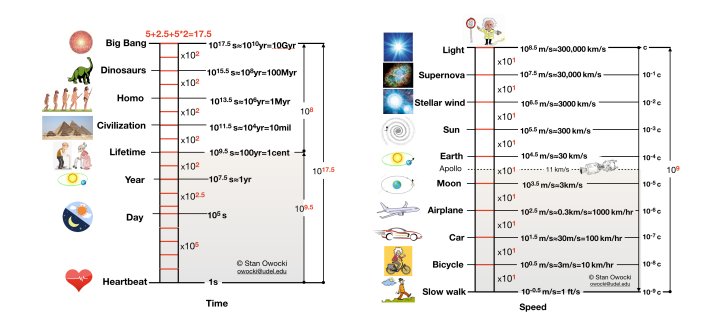

Figure 1.2: The enormous range of time scales and speeds encountered in astrophysics.

Time Scales

- • Nuclear reactions: 10⁻²² seconds

- • Atomic transitions: 10⁻⁸ seconds

- • Neutron star rotations: milliseconds

- • Earth's rotation: 24 hours

- • Earth's orbit: 1 year

- • Sun's lifetime: 10 billion years

- • Age of universe: 13.8 billion years

- • Red dwarf lifetimes: trillions of years

Velocity Scales

- • Solar system orbital motion: ~30 km/s

- • Sun around galaxy: ~220 km/s

- • Stellar escape velocities: ~600 km/s

- • Supernova ejecta: ~10,000 km/s

- • Neutron star surface: ~100,000 km/s

- • Galaxy peculiar velocities: ~1,000 km/s

- • Cosmic expansion (Hubble flow): 70 km/s/Mpc

- • Speed of light: 300,000 km/s (ultimate limit)

The Scientific Method in Astrophysics

Since we can't conduct controlled experiments on stars and galaxies, astrophysicists have developed a specialized approach:

- Observe: Collect electromagnetic radiation (light) across all wavelengths—from radio waves to gamma rays. Modern telescopes observe far beyond what our eyes can see.

- Measure: Extract quantitative data from observations— positions, brightness, colors, spectra, time variability, polarization.

- Infer Physical Properties: Use the laws of physics (gravity, thermodynamics, nuclear physics, quantum mechanics) to convert measurements into physical quantities.

- Build Models: Construct theoretical models based on fundamental physics to explain observations and make predictions.

- Test Predictions: Make new observations to test model predictions. If predictions fail, revise the model.

Example: Discovering an Element in the Sun Before Earth!

In 1868, French astronomer Pierre Janssen and English astronomer Norman Lockyer independently observed a bright yellow spectral line in sunlight during a solar eclipse. This line didn't match any element known on Earth at the time.

They named this mysterious element "helium" (from the Greek god Helios). It wasn't until 1895—27 years later—that helium was finally discovered on Earth! This demonstrates the power of spectroscopy: we literally discovered an element 93 million miles away before finding it at home.

What We'll Learn in This Course

In the chapters ahead, we'll learn how astrophysicists determine the fundamental properties of stars:

- Distance: How far away are stars and galaxies? (parallax, standard candles)

- Luminosity: How much energy does a star emit? (inverse-square law, magnitudes)

- Temperature: How hot is a star's surface? (color, Wien's law, spectral types)

- Radius: How big is a star? (Stefan-Boltzmann law)

- Composition: What is a star made of? (spectroscopy, absorption lines)

- Mass: How much does a star weigh? (binary systems, Kepler's laws)

- Age: How old is a star? (nuclear burning timescales)

- Motion: How fast and in what direction is it moving? (Doppler shift, proper motion)

Remember:

Everything we know about the universe beyond our solar system comes from analyzing light. Photons are our messengers, carrying information across vast cosmic distances. Learning to decode these messages is what astrophysics is all about!

For Graduate Students

Ready for research-level astrophysics? Explore advanced topics with full mathematical rigor:

Chapter 2: Measuring Distances in Space

The Distance Problem

Distance is the most fundamental measurement in astrophysics. Without knowing how far away something is, we can't determine its true size, brightness (luminosity), or mass. But measuring cosmic distances is extremely challenging—we can't stretch a ruler to the stars! Instead, astrophysicists have developed clever geometric and physical methods.

The Cosmic Distance Ladder:

Astronomers use different techniques for different distance scales, building on each method like rungs on a ladder. Nearby objects (solar system) use geometric methods, while distant galaxies require "standard candles"—objects of known luminosity.

Angular Size: The First Clue

When you look at an object in the sky, what you actually see is its angular size—how big it appears on the sky, measured in degrees, arcminutes, or arcseconds. This is NOT the same as its true physical size!

The Small-Angle Formula:

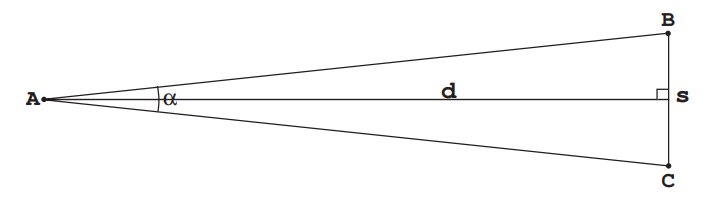

For objects much smaller than their distance (which is true for almost everything in astronomy), the angular size α, physical size s, and distance d are simply related:

where α must be measured in radians. Remember: 1 radian = 180/π ≈ 57.3° ≈ 206,265 arcseconds.

Mathematical Deep Dive: Deriving the Angular Size Formula

Optional - Skip if you're just starting out

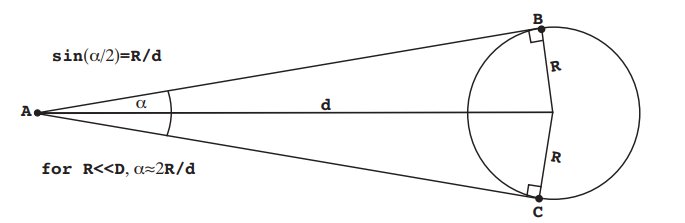

Consider an object of physical size s at distance d. From basic trigonometry, the angular size α (half-angle) satisfies:

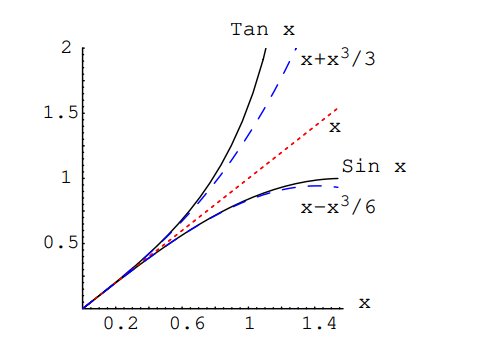

For astronomical distances where d ≫ s, the angle is very small (α ≪ 1 radian). We can use the Taylor expansion for small x: tan(x) ≈ x + x³/3 + ... For small angles, we keep only the first term:

This gives us the extremely useful small-angle approximation:

For Spherical Objects:

For a sphere of radius R at distance d, the exact relationship uses the sine function:

For small angles, sin(x) ≈ x - x³/6 + ..., so sin(α/2) ≈ α/2, giving us:

Example:

The Moon has an angular diameter of about 0.5° (30 arcminutes). Its physical diameter is 3,474 km, and it's about 384,000 km away. Check: 3,474 km / 384,000 km = 0.00905 radians ≈ 0.52°. It works!

Note: We need to convert degrees to radians for this formula (multiply degrees by π/180).

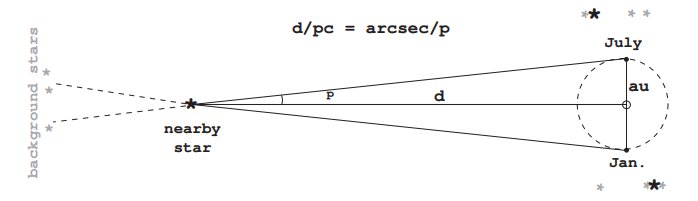

Parallax: The Gold Standard for Nearby Stars

Parallax is the apparent shift in position of a nearby object when viewed from different locations. Hold your thumb at arm's length and blink each eye alternately—your thumb appears to jump! This is parallax.

As Earth orbits the Sun, nearby stars appear to shift their positions relative to distant background stars. By measuring this tiny shift over 6 months (half an orbit), we can use trigonometry to calculate the star's distance.

The Simple Parallax Formula:

For a parallax angle p measured in arcseconds, the distance d in parsecs is simply:

Key conversions:

- • 1 parsec = 3.26 light-years

- • 1 parsec = 206,265 AU

- • 1 parsec = 3.086 × 10¹³ km

Mathematical Deep Dive: Deriving the Parsec

Optional - Skip if you're just starting out

Starting with the small-angle formula with baseline s = 1 AU and parallax angle p:

The parallax angle is measured in arcseconds, but we need radians for the formula. Converting using the fact that 1 radian = 206,265 arcseconds:

This defines the parsec (parallax-second): the distance at which a star has a parallax of exactly 1 arcsecond. At p = 1 arcsecond, d = 206,265 AU = 1 parsec. This gives us the practical formula:

The parsec is thus a natural unit for stellar distances, directly connected to the observable quantity (parallax angle) without needing unit conversions!

Figure 2.1: The parallax method uses Earth's orbit as a baseline to triangulate distances to nearby stars.

Proxima Centauri

Nearest star (besides the Sun)

Parallax: p = 0.768 arcsec

Distance: d = 1/0.768 = 1.30 pc = 4.24 light-years

Barnard's Star

Second nearest star system

Parallax: p = 0.547 arcsec

Distance: d = 1/0.547 = 1.83 pc = 6.0 light-years

The Problem with Parallax:

Parallax angles are incredibly tiny! Even the nearest star has a parallax less than 1 arcsecond—that's the apparent size of a coin seen from 4 km away. For distant stars, parallax becomes too small to measure accurately. ESA's Gaia satellite can measure parallaxes down to ~0.00002 arcseconds, reaching stars up to ~50,000 light-years away, but that's still just our local corner of the Milky Way.

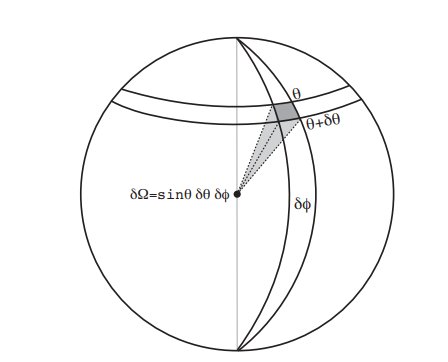

Solid Angle: Measuring 2D Angular Size

Extended objects cover a two-dimensional region on the sky. We characterize this with solid angle Ω, measured in steradians (the 2D analog of radians).

Simple Solid Angle Formula:

For a circular object with angular radius α (in radians):

Remember: There are 4π steradians in the full sky (just as there are 2π radians around a circle).

Mathematical Deep Dive: Solid Angle Derivation

Optional - Skip if you're just starting out

For an object with projected area A at distance d, the solid angle is:

For a circular disk of radius R, the area is A = πR². Using the small-angle approximation α = R/d:

General Definition Using Spherical Coordinates:

More formally, solid angle is defined using spherical coordinates (colatitude θ, azimuth φ). A small patch on the sky has area:

The solid angle subtended is the area divided by r², giving the element:

Integrating over the full sphere (θ: 0 to π, φ: 0 to 2π):

Converting to square degrees: 4π × (180/π)² = 41,253 deg².

Example: The Sun's Solid Angle

The Sun has angular radius α ≈ 0.25° = 0.0044 radians, so its solid angle is:

Ω ≈ π(0.25°)² ≈ 0.2 deg² = 6 × 10⁻⁵ steradians

This is about 1/200,000 of the full sky! The Moon has almost the same angular size and solid angle.

The Astronomical Unit (AU)

Before we can use parallax to measure stellar distances, we need to know the Earth-Sun distance (the baseline for our measurements). This distance is called the Astronomical Unit (AU).

Figure 2.2: Historical measurement of the Astronomical Unit using the transit of Venus across the Sun's disk.

Mathematical Deep Dive: Radar Ranging to Measure the AU

Optional - Skip if you're just starting out

Modern determination uses radar signals bounced off Venus. We measure the round-trip time Δt for radio waves traveling at the speed of light c:

This gives us the Earth-Venus distance in absolute units (km). To convert this to the AU (Earth-Sun distance), we need geometry. From Kepler's third law, we know Venus orbits at 0.72 AU from the Sun.

When Venus is at maximum elongation (47° from the Sun as seen from Earth), we have a triangle with: Earth-Sun = 1 AU, Venus-Sun = 0.72 AU, and Earth-Venus = d_EV. Using the law of cosines:

Solving for 1 AU in terms of the measured d_EV:

This technique, pioneered in the 1960s, gave the first precise measurement of the AU, accurate to within a few kilometers!

- Historical methods: Transit of Venus across the Sun (1761, 1769, 1874, 1882)—measure from different locations on Earth to triangulate Earth-Sun distance

- Modern radar ranging: Bounce radar off Venus (1960s) or near-Earth asteroids, measure round-trip light travel time with microsecond precision

- Modern value: 1 AU = 149,597,870.7 km (defined exactly since 2012)

Figure 2.3: Modern radar ranging technique - bouncing radio waves off planets and measuring the round-trip time.

Figure 2.4: Geometric relationship between parallax angle and distance - the foundation of stellar distance measurement.

Figure 2.5: The cosmic distance ladder - different techniques for measuring distances at various scales.

For Graduate Students

Ready for research-level astrophysics? Explore advanced topics with full mathematical rigor:

Chapter 3: Stellar Luminosity and Brightness

The Inverse-Square Law

One of the most important relationships in astronomy is how an object's apparent brightness depends on distance. Imagine a light bulb: at 1 meter it appears bright, but at 100 meters it looks much dimmer. This is because light spreads out as it travels!

Luminosity vs. Flux:

We distinguish between two concepts:

- Luminosity (L): The total power output of a star—energy emitted per unit time (erg/s or Watts). This is an intrinsic property.

- Flux (F): The energy per unit time per unit area received at distance d (erg/s/cm² or W/m²). This is what we observe.

For isotropic (uniform in all directions) emission, the luminosity spreads over a sphere of area 4πd²:

This is THE most important equation in observational astronomy! The flux decreases as the inverse-square of distance.

The Standard Candle Method:

If we know a star's luminosity L (making it a "standard candle") and measure its flux F, we can calculate the distance:

Conversely, if we know the distance (from parallax), we can determine the luminosity:

Example: The Solar Luminosity

At Earth (d = 1 AU = 1.5 × 10¹³ cm), we measure the solar flux (called the "solar constant"):

F = 1.4 × 10⁶ erg/cm²/s = 1.4 kW/m²

Using the inverse-square law:

L = 4π(1.5 × 10¹³)² × (1.4 × 10⁶) = 4 × 10³³ erg/s = 4 × 10²⁶ W

The Sun emits as much power as 4 million billion billion 100-watt light bulbs! We use L as the benchmark for stellar luminosities, which range from L/1000 for red dwarfs to 10⁶L for blue supergiants.

Surface Brightness: Distance-Independent!

For resolved objects (where we can measure angular size), there's a surprising result: the surface brightness stays constant with distance!

Surface Brightness (Intensity):

Surface brightness I is flux per solid angle Ω:

where F* = L/4πR² is the flux at the stellar surface. Notice: d cancels out!

The flux decreases as 1/d², but the solid angle also decreases as 1/d². The ratio remains constant. The Sun has the same surface brightness whether viewed from Earth or from its own surface (ignoring atmospheric absorption)—though the solid angle changes from 6×10⁻⁵ steradians to 2π steradians!

The Magnitude System

Astronomers use a logarithmic scale called "magnitude" to describe brightness, dating back to ancient Greek classifications. It has awkward conventions, but it's universally used!

Apparent Magnitude (m):

The brightness we observe. A difference of 5 magnitudes = factor of 100 in flux. The relationship is:

Note: Larger magnitude = dimmer object! Sirius (brightest star) has m = -1.4; faintest naked-eye stars have m ≈ 6.

Absolute Magnitude (M):

The apparent magnitude a star would have at the standard distance of 10 parsecs. This removes distance effects and characterizes intrinsic luminosity.

The Sun has M = +4.8. More luminous stars have smaller (more negative) absolute magnitudes.

Mathematical Deep Dive: Deriving the Distance Modulus

Optional - Skip if you're just starting out

Starting with the inverse-square law and the magnitude definition:

where F_m is the flux at distance d and F_M is the flux at the standard distance of 10 pc. Using F = L/4πd²:

Substituting back:

Simplifying (noting that log(100) = 2):

This is called the distance modulus and is one of the most practical formulas in astronomy. If you know apparent magnitude m (observable) and absolute magnitude M (intrinsic luminosity), you can solve for distance d!

Light: Our Cosmic Messenger

Almost everything we know about the universe comes from light. Light carries information across vast distances of space, arriving at our telescopes after journeys that sometimes span billions of years. But "light" is more than just what our eyes can see!

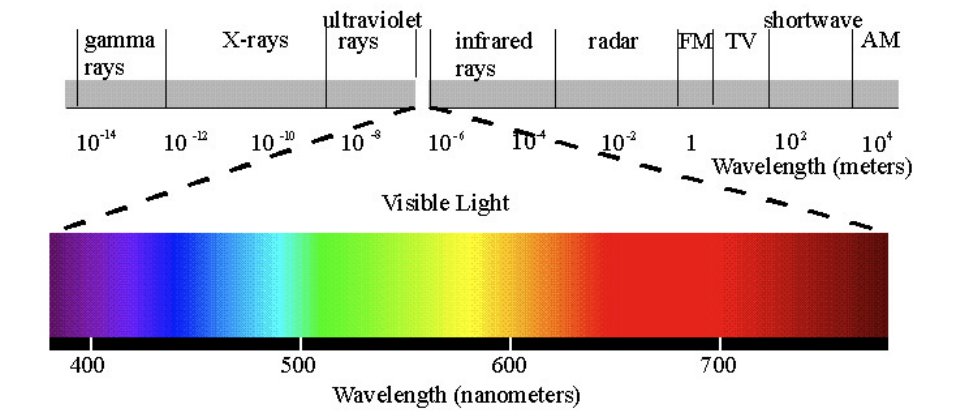

The Electromagnetic Spectrum

Visible light—the rainbow of colors from red to violet—is actually just a tiny sliver of the full electromagnetic spectrum. All of these are the same thing (electromagnetic waves), just with different wavelengths and energies:

📻 Radio Waves (longest wavelength)

Wavelength: meters to kilometers • Used for: Studying cold gas clouds, pulsars, cosmic microwave background

🌡️ Microwaves

Wavelength: millimeters to centimeters • Used for: Cosmic background radiation, molecular clouds

🔥 Infrared

Wavelength: micrometers • Used for: Seeing through dust, cool stars, distant galaxies, planet formation

👁️ Visible Light

Wavelength: 400-700 nanometers • Red, orange, yellow, green, blue, violet • What our eyes see!

☀️ Ultraviolet

Wavelength: tens of nanometers • Used for: Hot stars, stellar atmospheres, high-energy processes

⚡ X-rays

Wavelength: 0.01-10 nanometers • Used for: Black hole accretion disks, neutron stars, supernovae

💥 Gamma Rays (shortest wavelength)

Wavelength: picometers • Used for: Most energetic events—gamma-ray bursts, nuclear reactions in stars

Remember:

Longer wavelength = lower energy • Shorter wavelength = higher energy

Radio waves are mellow; gamma rays pack a punch!

Why Different Wavelengths Matter

Different cosmic objects and processes emit light at different wavelengths:

- Cool objects (like dust clouds, planets, brown dwarfs) emit mostly infrared radiation

- Medium-temperature objects (like our Sun) emit visible light

- Hot objects (like blue stars) emit lots of UV light

- Extremely hot regions (like near black holes) emit X-rays

- Ultra-high-energy events (like supernovae cores) emit gamma rays

By observing objects at different wavelengths, we get a complete picture—like how a thermal camera and a regular camera show you different things about the same scene!

What Light Tells Us

Astrophysicists are like forensic investigators, extracting clues from light:

🌡️ Temperature

Hot objects glow blue-white; cooler ones glow red. By measuring color, we can determine temperature.

🧪 Chemical Composition

Different elements absorb and emit light at specific wavelengths (spectral lines). It's like a chemical fingerprint!

🚗 Motion (Doppler Shift)

Objects moving toward us have their light shifted to shorter wavelengths (blueshift); objects moving away are redshifted. This tells us velocities!

📏 Distance

Using standard candles (objects with known luminosity) and measuring how bright they appear, we can calculate how far away they are.

Amazing Example:

In 1868, astronomers detected a new spectral line in sunlight that didn't match any known element on Earth. They named it "helium" (from Helios, Greek for Sun). Only later was helium discovered on Earth! We literally discovered an element in the Sun before finding it at home.

For Graduate Students

Ready for research-level astrophysics? Explore advanced topics with full mathematical rigor:

Chapter 4: Temperature, Color, and Spectra

Why Do Stars Shine?

Stars shine because their surfaces are incredibly hot! The thermal radiation from hot atoms produces the light we see. This "thermal radiation" arises from the violent collisions of atoms and electrons at high temperatures, measured in Kelvin (K = °C + 273). The Sun's surface is about 5,800 K—hot enough to melt any known material!

The Wave Nature of Light

In the 19th century, James Clerk Maxwell showed that light is an electromagnetic (EM) wave. Light waves are characterized by wavelength λ, frequency ν, and travel at speed c:

Fundamental Wave Relation:

where:

- • λ = wavelength (distance between wave crests)

- • ν = frequency (oscillations per second)

- • c = 3 × 10⁸ m/s = 3 × 10¹⁰ cm/s (speed of light)

Quantization of Light: Photons

In the early 20th century, Einstein and Planck discovered that light is quantized into discrete particles called photons. Each photon carries energy:

Photon Energy:

where h = Planck's constant = 6.6 × 10⁻²⁷ erg·s = 6.6 × 10⁻³⁴ J·s

Key insight: Shorter wavelength = higher frequency = higher energy per photon. Blue photons carry more energy than red photons!

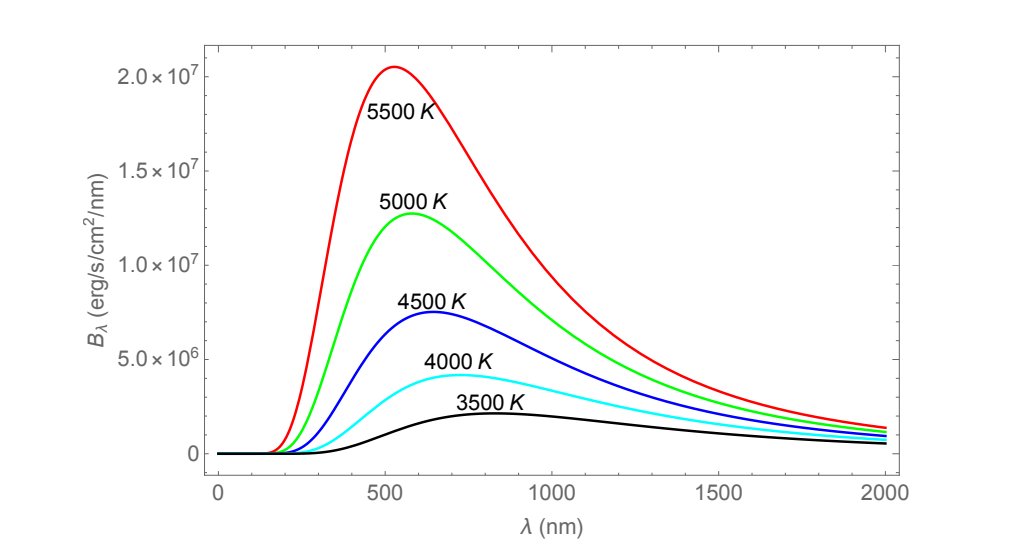

The Planck Black-Body Spectrum

When matter reaches thermodynamic equilibrium at temperature T, it emits thermal radiation described by Planck's black-body function. This depends ONLY on temperature, not on density, pressure, or composition!

The Planck function peaks at different wavelengths for different temperatures. Hot objects peak at short (blue) wavelengths; cool objects peak at long (red) wavelengths.

Mathematical Deep Dive: The Planck Function

Optional - Skip if you're just starting out

Planck derived the exact formula for thermal radiation by combining quantum physics with statistical mechanics. The result is the Planck function in wavelength form:

where:

- • h = Planck's constant = 6.6 × 10⁻²⁷ erg·s

- • c = speed of light = 3 × 10¹⁰ cm/s

- • k = Boltzmann constant = 1.38 × 10⁻¹⁶ erg/K

- • T = temperature in Kelvin

- • λ = wavelength

B_λ has units of intensity (surface brightness): erg/cm²/s/steradian/nm. It represents the energy emitted per unit time, per unit area, per unit solid angle, per unit wavelength interval.

The denominator contains an exponential that depends on the ratio hc/λkT. This ratio compares the photon energy (hc/λ) to the thermal energy (kT). When photon energy ≫ thermal energy (short wavelengths or low temperatures), the exponential dominates and emission drops off rapidly (Wien tail). When photon energy ≪ thermal energy (long wavelengths or high temperatures), the function simplifies to the Rayleigh-Jeans law.

This single formula revolutionized physics and led directly to the development of quantum mechanics!

Wien's Displacement Law

The wavelength λmax at which the Planck function peaks is inversely proportional to temperature:

Wien's Law:

Or in more convenient form:

where T = 5,800 K. The Sun's spectrum peaks at λmax ≈ 500 nm (green), right in the middle of the visible spectrum. Not coincidental—our eyes evolved to see the wavelengths where sunlight is brightest!

Example: Stellar Temperatures from Color

Hot blue star: λmax = 250 nm (UV) → T = 2.9×10⁶/250 = 11,600 K

Cool red star: λmax = 1000 nm (near-IR) → T = 2.9×10⁶/1000 = 2,900 K

Just by measuring where a star's spectrum peaks, we can estimate its surface temperature!

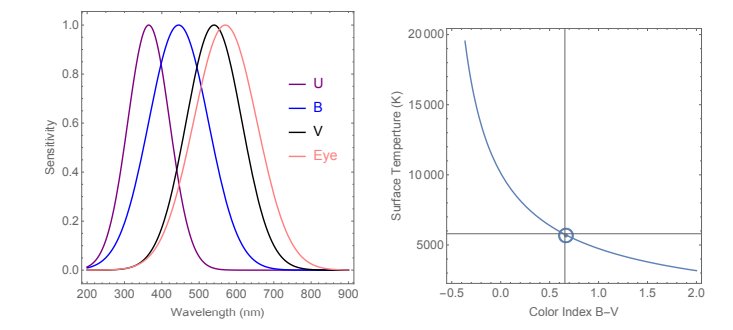

Photometric Colors

In practice, measuring the full spectrum is time-consuming. Instead, astronomers use standardized color filters (like UBV: Ultraviolet, Blue, Visible) to measure brightness in different wavebands. The color index B-V (blue magnitude minus visible magnitude) directly indicates temperature.

Color-Temperature Relationship:

- B-V < 0: Blue stars, T > 10,000 K

- B-V ≈ 0.66: Sun-like stars, T ≈ 5,800 K

- B-V > 1.5: Red stars, T < 4,000 K

Positive B-V means less bright in blue than visible → cooler, redder star. Negative B-V means brighter in blue → hotter, bluer star.

Basic Physics: Gravity and Energy

Good news: the laws of physics that work here on Earth also work everywhere in the universe! Whether you're on Jupiter's moon Europa or in a galaxy far, far away, gravity, energy, and motion all follow the same rules.

Gravity: The Cosmic Glue

Gravity is the dominant force shaping the universe at large scales. It's what holds you to Earth, keeps Earth orbiting the Sun, binds stars into galaxies, and makes the universe expand and evolve.

Figure 4.1: Newton's law of universal gravitation - the inverse square law that governs celestial mechanics.

Newton's Law of Gravitation:

Every object with mass attracts every other object with mass. The force gets stronger with more mass and weaker with distance:

Where G is the gravitational constant, m₁ and m₂ are the masses, and r is the distance between them.

This simple equation explains why:

- Planets orbit stars in ellipses (Kepler's laws)

- Moons orbit planets

- The tide comes in and out (Moon's gravity on Earth)

- Stars cluster into galaxies

- The universe itself is shaped by gravity

But wait, there's more!

Newton's gravity works great for most situations, but Einstein showed that gravity is actually the curvature of spacetime itself. For ultra-strong gravity (near black holes) or very precise measurements (GPS satellites), we need Einstein's General Relativity. We'll explore this more in Part IV!

Energy: The Cosmic Currency

Energy is the ability to do work. It comes in many forms, and crucially, it can't be created or destroyed—only transformed from one form to another. This is the Law of Conservation of Energy.

⚡ Kinetic Energy

Energy of motion. A speeding asteroid has tremendous kinetic energy!

⛰️ Potential Energy

Stored energy due to position. A rock at the top of a hill, or a star far from a black hole.

🔥 Thermal Energy

Heat—the random motion of atoms and molecules. Stars are incredibly hot!

☀️ Radiative Energy

Energy carried by light and other electromagnetic radiation.

💥 Nuclear Energy

Energy stored in atomic nuclei. This is what powers stars!

🌌 Mass-Energy

Einstein's famous E = mc² shows that mass itself is a form of energy.

E = mc²: The Most Famous Equation

Einstein's equation tells us that mass and energy are equivalent—you can convert one to the other. The "c²" is the speed of light squared, a huge number, which means even a tiny bit of mass contains an enormous amount of energy.

Figure 4.2: Einstein's mass-energy equivalence E=mc² - the source of stellar power through nuclear fusion.

This Equation Explains:

- • Why stars can shine for billions of years (converting hydrogen mass to energy)

- • Why nuclear bombs are so powerful (converting tiny amounts of mass to huge energy)

- • Why particle accelerators work (creating particles from pure energy)

- • Why black holes can emit radiation (Hawking radiation)

Cosmic Distances and Units

Space is big. Really big. So big that normal units like kilometers become absurdly cumbersome. Astrophysicists use special units:

💡 Light-year

The distance light travels in one year ≈ 9.46 trillion kilometers

Example: The nearest star (Proxima Centauri) is 4.2 light-years away

📏 Astronomical Unit (AU)

The distance from Earth to the Sun ≈ 150 million kilometers

Example: Jupiter is about 5 AU from the Sun

📐 Parsec (pc)

Based on parallax measurements ≈ 3.26 light-years (astronomers prefer this to light-years)

Example: The galactic center is about 8,000 parsecs (8 kiloparsecs) away

🌌 Megaparsec (Mpc)

One million parsecs ≈ 3.26 million light-years (used for distances between galaxies)

Example: Andromeda Galaxy is about 0.77 Mpc away

Mind-Bending Scale:

If the Sun were the size of a basketball:

- • Earth would be a grain of sand 25 meters away

- • Jupiter would be a marble 130 meters away

- • The nearest star would be 6,700 kilometers away (Los Angeles to Paris!)

- • Our galaxy would be 100 million kilometers across

Time Scales in the Universe

Just as space is vast, cosmic time scales are immense:

Figure 4.3: The enormous range of time scales in the universe - from atomic processes to the age of the cosmos.

- Human lifetime: ~80 years

- Recorded human history: ~5,000 years

- Age of modern humans: ~300,000 years

- Age of dinosaurs: ~165 million years

- Age of Earth: ~4.5 billion years

- Age of the Universe: ~13.8 billion years

- Lifetime of a red dwarf star: trillions of years (longer than current age of universe!)

For Graduate Students

Ready for research-level astrophysics? Explore advanced topics with full mathematical rigor: